Army Cleaning Weapons It Cleans the Weapons Once Again

The job of an international chemical weapons inspector is i of the most dangerous in the earth. Inspectors accept to seek out some of the almost poisonous substances known to mankind and dismantle bombs filled with deadly nerve gas. So it is remarkable that, later on more than two decades of chemic weapons devastation, not a single inspector has been killed.

But Syria presents a new kind of challenge. For if the The states and Russian federation strike a deal at Geneva and the government of president Bashar al-Assad does not rescind its application to join the chemical weapons convention (CWC), the inspectors could soon be embarking on a task that has never been attempted: convincing a state of its weapons of mass devastation in the midst of a state of war.

In the few days inspectors were on the ground in Damascus looking for evidence of the 21 Baronial poison gas attack, they came under sniper fire that put i of their vehicles out of activeness and confined them to their hotel for a twenty-four hour period.

The task of tracking down, verifying and so destroying mayhap more than one,000 tonnes of mustard gas and nerve agents scattered over scores of military sites will be complex, fourth dimension-consuming and risky. But the one-half dozen electric current and old inspectors interviewed past the Guardian all argued it is worth trying.

"Simply getting Syria to join the chemical weapons convention is an enormously of import and historic step frontwards," said Paul Walker, the programme director at Green Cantankerous International advancement grouping and a veteran of the 2-decade effort to destroy Us and Russian chemic weapons. "Once you accept the sites highly secured, inspected and locked down under seal that is another big stride forwards. Then if the weapons are used again in that location would be huge consequences."

Jean Pascal Zanders, who runs The Trench, a research and consultancy initiative focusing on disarmament, said: "We really are in uncharted territory hither, and there is going to be a need for inventiveness … only if countries work together it is doable. The mechanisms exist and the engineering exists."

If a deal is done, the first inspectors to country in Damascus are likely to be drawn from the multinational roster of 126 working for the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The Hague-based agency is little known compared with its nuclear cousin, the International Atomic Free energy Agency, only in its xvi years, information technology has overseen the destruction of more than 70,000 tonnes of chemical weapons in vii countries, eliminating the entire arsenals of Republic of albania, South Korea and India, and almost the whole stockpiles of the The states and Libya. The vast Russian arsenal inherited from the Soviet Union is most two-thirds destroyed.

Syria is due to become a state party to the CWC on 11 Oct, 30 days after the president sent his application alphabetic character to the UN on Thursday. Syrian arab republic would then exist legally spring past the convention prohibiting production, stockpiling or use of chemic weapons.

The authorities in Damascus would so have another 30 days (the US and its allies will argue for an accelerated timetable) to produce a full annunciation of all its chemic agents, both in weapons and in bulk storage, besides as forerunner chemicals, production facilities and delivery systems. Information technology is that proclamation that the OPCW inspectors would take to Damascus.

From the airport, they would fan out under war machine guard to the chemical weapon sites. Alongside its declaration the authorities would accept to provide a detailed plan for getting inspectors safely to the sites. As the most significant of these locations are expected to be regular army bases in government-controlled territory, this initial mission will not involve crossing front lines and should therefore not exist equally precarious as the last Damascus mission. But the risks would all the same be substantial.

"The big trouble for the OPCW is to what extent are they going to risk the lives of their inspectors to monitor the process," Zanders said. "The security guarantees are going to be paramount."

Once on site, the inspectors would draw up an inventory, counting canisters of nerve agents and precursor chemicals, equally well as shells, rockets and aerial bombs with chemical payloads. Every particular would be assigned a barcode and a seal would be fastened that would sound an alert if tampered with. The inspectors would set up cameras to monitor the site remotely.

At that point – possibly well before the end of the year – at to the lowest degree some of the Syrian arsenal would exist under international control, in the sense in that the OPCW and its member states would know if the weapons were moved or used.

"Once everything is inventoried and sealed you can give a sigh of relief," said Matthew Meselson, a chemical and biological artillery skilful at Harvard Academy. "Demilitarisation will be a long-term process after that, simply in the beginning few weeks you volition have cleaved the back of the problem, because once anyone tried to take the weapons there would be a big international reaction."

Two huge challenges would remain. The international customs would have to cheque whether the Syrian announcement was complete, a process that the Iraqi experience suggests could take years. Second, at that place would be the long procedure of destruction.

Paradoxically, the CWC has made it harder to become rid of chemic weapons. Before it came into upshot in 1997, munitions were ofttimes tossed into the body of water. Baltic fisherman and Polish holidaymakers are still being burned by the thousands of mustard gas shells Britain, Frg and the Soviet Union dumped in the Gotland Deep after the 2nd globe war.

The improvised methods used in Iraq in 1991, blowing up and burning chemical bombs in deep pits, are besides non immune under the CWC for environmental reasons. Nor is the shipping of chemical munitions or agents exterior state borders.

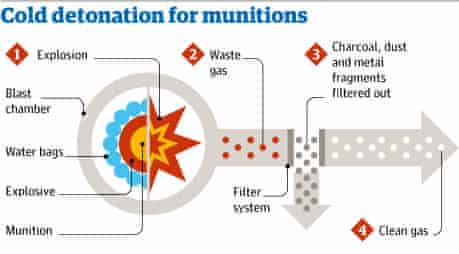

There are now 2 major strategies for destroying munitions that are filled with chemical agents. The first is cold detonation. Here, the munition is surrounded with explosives – and sometimes water bags – and put in an armour-plated nail chamber, or "bang box".

On detonation, the explosion destroys the munition and the amanuensis inside. The water bags blot some of the boom and fill the chamber with steam, which helps break downward any residual amanuensis. The waste is pumped through filters, oxidisers and beds of carbon to remove acidic and organic vapours, soot and grit. The organisation has been tested at United kingdom's Porton Downwards facility and no agent vapours were found in the vented gas. A large organisation tin can handle about forty munitions in 10 hours. It is transported on eight 40ft trailers.

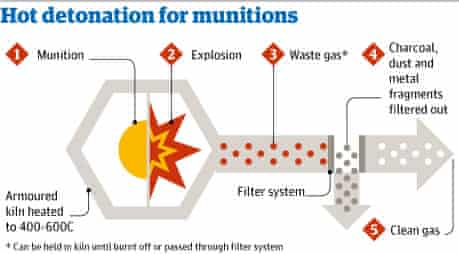

The 2d approach is hot detonation. The munitions are place in a kiln at 600C. The munition explodes in the heat and waste gases are held inside long enough to break them down or sent through filters and scrubbers to clean them. The system was used to destroy 16 tonnes of mustard gas the Albanian government found in 1997 left over from the communist era. The process took about six months but well-nigh began in tragedy when the first canister incinerated in 19 seconds instead of the 19 minutes expected, blowing out the lesser of the containment vessel. But the method has been refined somewhat since so. The Swedish company, Dynasafe, has a mobile version that is carried on three flatbed trailers.

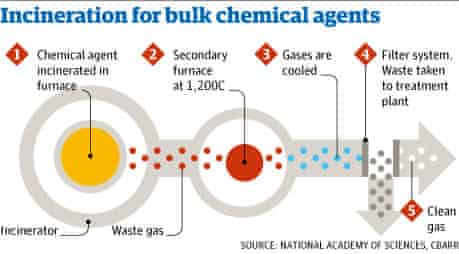

Bulk stores of chemical agents that have not been loaded into weapons are simpler to bargain with. Most of the US stockpile of chemical weapons has been destroyed with incineration. The intense estrus and air oxidises the chemical agents into carbon dioxide and water, though amounts of nasty chemicals remain, such every bit furans and dioxins, which have to be filtered out. Other liquid and solid waste tin can be sent to a commercial hazardous waste treatment plant. Portable incinerators have been built, merely rarely deployed.

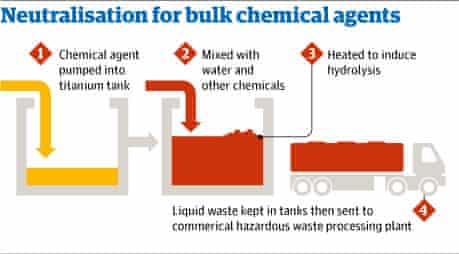

Neutralisation, the cheaper procedure favoured by the Russians, uses water and chemicals to convert warfare agents into more beneficial substances. This was used to destroy nerve agents, including tabun and sarin, at production facilities in Iraq in the early 1990s. The Iraq constitute processed more a tonne of chemicals per mean solar day, but the waste product contained sodium cyanide and had to be stored in steel tanks sealed in concrete bunkers. The US has built what it calls a field deployable hydrolysis organization, which can be flown to a site and fabricated ready inside 10 days. Within a titanium tank, chemical agents are mixed with water, sodium hydroxide and other chemicals, and then heated to divide them autonomously. The facility can process about 25 tonnes of amanuensis a mean solar day.

With such new portable technology, the bulk of the Syrian arsenal could conceivably exist destroyed within a year, and then long every bit information technology were possible to motion the weapons safely to a handful of sites that could be kept secure.

But Ralf Trapp, a German former OPCW official, believes the task is worth starting, fifty-fifty if its completion appears afar. "All parties would have to work together to come up upward with arrangements, and that is a positive thing," Trapp said. "The alternative is to leave the stuff alone, and that is most an invitation to use it again."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/13/destroying-chemical-weapons-syria-challenge

0 Response to "Army Cleaning Weapons It Cleans the Weapons Once Again"

Post a Comment